Portfolio Insight | 3rd Quarter 2022

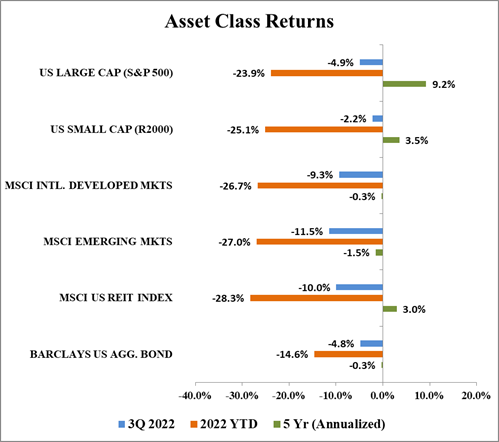

Stubbornly high inflation and a Federal Reserve belatedly determined to bring it down, even if it causes a recession, pushed markets lower for the third quarter in a row. The bear market continued, with the S&P 500 returning -4.9% in the third quarter to bring its YTD loss to -23.9%.

The top performing sectors in the third quarter were Consumer Discretionary, Energy, and Financials, while those that underperformed the most were Communication Services, Real Estate, and Materials. Large cap growth names (-29.5%) continue to trail large cap value names (-16.8%) in 2022 as interest rates have moved materially higher and impacted higher multiple stocks.

Up and Down

Following the very weak first half of the year, the S&P 500 staged a fairly strong but short-lived rally after the Fed’s 0.75% interest rate hike on June 15. Some traders interpreted Chairman Powell’s press conference comments to mean that that Fed might be “pivoting” on the upward trajectory of interest rates, even though there was not a clear announcement of such impending action. Other traders believed that inflation had peaked because core (excluding Food & Energy) Consumer Price Index (CPI) growth slowed in June, and gasoline prices had started to fall. The market moved up 12% from the end of June until mid-August, at which point it proceeded to roll over. A worse than expected inflation report on September 13 accelerated the downturn, and by the end of the quarter, the market had knifed down to a new 2022 low.

The market tends to follow earnings, and in a shift from earlier this year, we are now seeing probable lower demand, persistent inflation, and a strong dollar pushing expectations for US corporate profits lower. Also, as interest rates rise, the discount rate applied to future cash flows rises as well, thus hurting valuation multiples. Higher interest rates and slowing earnings growth are the primary reasons for the decline in the market so far in 2022.

Fed Wish Granted

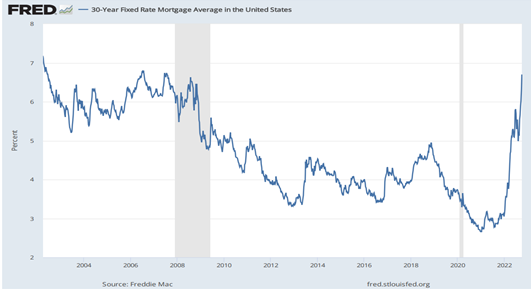

The dual mandate of the Federal Reserve is to achieve maximum employment and price stability (generally held to be a 2% long-term inflation rate). At this time, employment remains very strong, but the CPI sits near a 40-year high. So, to slow growth and tamp down inflation, the Fed has raised interest rates by 3% in 2022 and has commenced the reduction of its holdings of government debt (reducing its balance sheet). These actions are already stressing the economy, perhaps most notably in the housing sector, which is being slowed by 30-year mortgage rates that have more than doubled since the beginning of the year, hitting levels last seen in 2007:

The unemployment rate is still low at 3.7%, but the Fed anticipates this rising to 4.4% next year, which will likely affect heretofore resilient consumer confidence and spending. Large tech companies like Microsoft and Alphabet are dramatically slowing hiring, and other firms like Ford and Peloton have commenced layoffs.

Goodbye TINA

One of the drivers of very strong equity market returns over the last several years has been the lack of attractive alternatives such as fixed income and cash, a state of affairs sometimes described with the acronym “TINA” (There Is No Alternative). With interest rates pinned near zero for most of the period since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the risk/reward of bonds seemed poor, and investors could not earn a reasonable return holding cash instruments. That situation has changed dramatically in 2022. With interest rates rapidly climbing, the risk/reward in fixed income has become more favorable, and equity investments now have more competition for investor flows. This has presented an environment ripe for filling out balanced portfolios with high quality fixed income investment, both US Treasuries as well as corporate bonds.

Domestic Equity Outlook

Until we see a string of monthly inflation prints that are showing clear (and ideally, better than expected) deceleration as well as a line of sight towards the Fed’s 2% target, it will be difficult to declare a definitive bottom in the market. However, there is evidence that the Fed’s monetary policy actions are having the intended impact and that inflation has possibly peaked.

Continued high volatility and muted gains are likely to persist from here through year end as the market digests new inflation reports as well as Fed actions and commentary. On the bright side for long-term investors, sentiment remains highly negative (contrarian indicator) and the market is oversold, presenting outstanding opportunities. Many high quality companies have seen their stocks fall below what is likely to be long-term true value, simply because of higher interest rates and lower valuation multiples. Therefore, the risk/reward for long-term equity investors appears highly favorable, once interest rates peak and the overall earnings outlook brightens.

Fixed Income Outlook

The sustained rise in interest rates has continued to pressure bond prices throughout 2022. The Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index, a mix of government and corporate bonds, has declined 14.6% YTD. 10-year Treasury yields have moved from 1.52% at the beginning of the year to 3.83% at quarter-end. Given our shorter maturity positioning, our bond holdings have held up meaningfully better than the index.

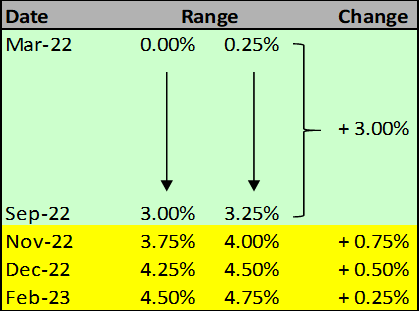

Persistently high inflation is the primary culprit for the rise in rates. While there have been signs of softening inflationary pressures (lower gasoline prices, used car prices, etc.), the pace of improvement for other categories (food, rents, wages, etc.) has been worse than many, the Federal Reserve in particular, expected. The Fed’s primary focus today is to avoid an extended high inflation environment like the US saw for most of the 1970s and early 1980s. Fortunately, longer-term inflation expectations (next 5-10 years) remain well anchored towards recent lower historical levels (2.0% – 2.5%). As a result, the Fed has continued to aggressively hike interest rates with the hopes of cooling demand, and is likely to continue to do so through early next year. As you can see in the table below, the Fed has already raised short-term interest rates from effectively zero earlier this year to the current range of 3.00% – 3.25%. Market expectations, which are also currently reflected in shorter-term Treasury yields, imply an additional 1.50% of Fed interest rate hikes. In the event the Fed is successful in lowering inflation but the US economy does begin to sputter, it is possible that the Fed could begin to cut rates later in 2023.

Fed Target Rate – Fed Fund Futures

The effect of higher rates has already begun to filter through the US economy. As mentioned earlier, the housing market is facing pressure from sharply higher mortgage rates. A similar picture has emerged for vehicle sales as well. The concern for investors is that the Fed will move rates too high and ultimately push the US economy into a major recession. Ideally, the Fed will finish its rate hiking cycle over the next several months, and then pause as inflationary pressures decline and the US economy experiences only a mild recession or perhaps avoids one altogether. However, the higher the Fed raises rates, the greater the risk of a more severe recession.

As a result of the move in interest rates, we have continued to buy both high quality corporate and US Treasury bonds for clients with fixed income allocations. These bonds currently have yields in the 4.0% – 5.5% range with maturities of 1 – 4 years. Top quality bonds have not seen yields this high in over a decade (outside of a brief period in early 2020 as investors panicked during COVID-19). Positions bought earlier in the year may show modest losses as interest rates have continued to move higher after our purchase. However, since we plan to hold each of these bonds to maturity, those losses should reverse over time as investors receive full principal and interest.

Global Markets Outlook

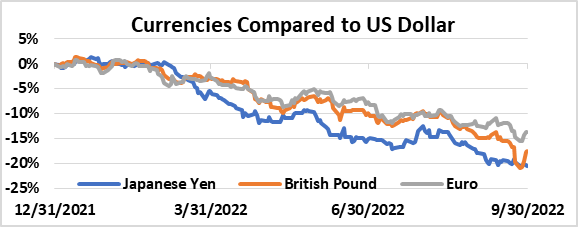

Large US stocks (S&P 500) significantly outperformed their non-US counterparts in the third quarter, due in large part to a rapid increase in the value of the US dollar. For the quarter, US stocks were down 4.9% whereas international developed markets dropped 9.3% and emerging markets fell 11.5%. YTD, large US stocks have also held up somewhat better, returning -23.9% compared to -26.7% for international developed markets and -27.0% for emerging markets. The US dollar exceeded 1:1 parity with the Euro for the first time in 20 years and achieved a record high against the British Pound amid uncertainty about the health of the UK economy, until the Bank of England intervened to stabilize its financial markets. Japan also acted to support the yen for the first time since 1998.

With the US economy holding up better than peers and the US Federal Reserve hiking rates aggressively, the US Dollar Index (DXY) was up 10% during the quarter:

A stronger dollar makes importing goods more expensive for non-dollar countries, many of whom are already suffering from acute energy price increases. Additionally, a strong dollar raises borrowing costs, making it more expensive to pay off dollar denominated debt. Furthermore, the dollar has traditionally been a safe haven in times of crisis, which has helped US markets outperform international markets in past recessions.

For US multinational corporations, the strengthening dollar hurts revenues and profits as the companies convert less valuable foreign currency into dollars. On the other hand, an appreciating dollar increases the purchasing power of US consumers spending overseas while also having a deflationary impact on those companies that import goods and services. In the near term, a significantly weaker dollar appears unlikely. The Fed would likely need to pivot, which it might not do until we are in an obvious recession and inflation is clearly heading down towards the target rate.

After recent underperformance, international stocks are trading at a historically large discount to US stocks. Unfortunately, the valuation gap has been wide for a considerable amount of time, so a historically wide discount does not guarantee outperformance. To reverse this trend, there likely needs to be steady outperformance of value stocks and a stabilization or depreciation of the US dollar against other currencies. While valuation alone is not predictive of short-term performance, it has a good track record predicting long-term performance. Thus, the prospects for long-term international outperformance remain favorable.

REIT Commentary

In the third quarter of 2022, the MSCI US REIT Index produced a total return of -10.0%. All of the damage was done in the last 18 days of the quarter when the index fell by 16% due to the rise in the 10-year Treasury yield to a 12-year high of 3.83%. While real estate fundamentals should be a beneficiary of the same inflation that is causing the rapid rise in the 10-year Treasury yield, the selloff of risk assets has spared few asset classes. We still believe cash flow and dividend growth will finish the year in the high single digits, followed by similar growth in 2023, which will eventually be recognized by investors when the 10-year Treasury yield stabilizes.

In response to concerns the real estate market could be heading for another 2008 style correction, it is very important to remember that “today’s REIT” is nearly unrecognizable compared with the average REIT heading into the financial crisis. Indeed, 2008 included a multitude of painful lessons for REIT management teams, but thankfully, the industry has transformed over the past decade.

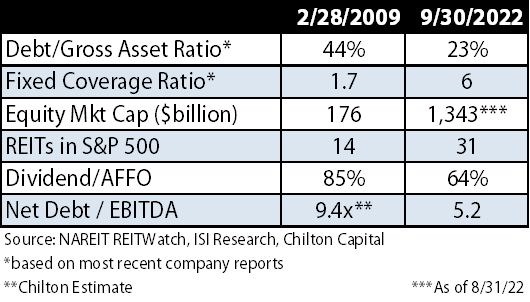

First and foremost, dividend payout ratios hover around 64% of cash flow today (as measured by

Adjusted Funds From Operations, or AFFO), which compares to 85% in 2008. With most REITs having reset their dividends to the minimum allowable level in 2020, most REITs will actually be forced to increase their dividends in 2022 in order to maintain REIT status given the positive growth in cash flow (we estimate a weighted average AFFO growth rate of +12% for 2022 in the REIT Composite). Similarly, REIT Debt to Gross

Asset Value (or D/GAV) has declined to 23% versus 44% in early 2009, which we believe essentially takes bankruptcy risk off the table. Finally, weighted average maturity of debt has increased from 5 years in 2008 to over 7 years as of July 31, so very little REIT debt is maturing in the next 18 months, which should prevent any significant earnings dilution from refinancing.

REITs Have Been De-Risked

As of September 30, REITs are trading at a 20% discount to net asset value (or “NAV”, a measure of the private market value of REIT assets net of liabilities), which means that their assets could be sold for 25% more on the private market than they are priced in the public market. In addition, REIT leverage of 23% compared to average leverage of 41% in the private market according to the NCREIF National Property Index (or “NPI”) as of March 31. Furthermore, data from non-traded REIT (or “NTR”) data provider BlueVault shows that the average NTR had floating rate debt exposure of 58% as of March 31, which compared to public REITs at 13.5%. With significantly higher debt, more floating rate debt exposure, and a valuation 25% above public REITs, we are hard-pressed to imagine any scenario where private real estate outperforms public REITs in the near or even intermediate-term. In our opinion, every private real estate investor should be investing cash into public REITs in anticipation of the narrowing of this wide valuation gap; in some cases, depending on the tax consequences, a valuation gap this wide would warrant selling private real estate and reinvesting the proceeds into public REITs.

Bradley J. Eixmann, CFA

Brandon J. Frank

Robert J. Greenberg, CFA

Matthew R. Werner, CFA